By the rivers of Babylon—there we sat down and there we wept when we remembered Zion. On the willows there we hung up our harps. For there our captors asked us for songs, and our tormentors asked for mirth, saying, “Sing us one of the songs of Zion!”

How could we sing the Lord’s song in a foreign land?

Psalm 137:1-4

Those caught up in the cycle of incarceration have been knocked around by life. Most, if not all, were first victims themselves, but lacked the resources and opportunity to heal from their trauma. It is not surprising, therefore, that the cycle would continue from one generation to the next. Hurt people hurt people. The conditions that contribute to incarceration include racism, poverty, abuse, addiction, violence, mental illness, homelessness, and inadequate education. Family systems are often permeated with such dynamics. Young people in such environments are not taught proper life skills to cope with adversity and challenge; instead they learn to strike out and to become the aggressor. Many, if not all, grow up in shame. Many grow up without fathers. Others are shown unhealthy models by parents who themselves were caught up in the same cycle of trauma. It’s cyclical and generational. It becomes the expected norm, the lot in life.

My own family was imprisoned by the four dreadful demons of poverty, alcoholism/drug addiction, domestic violence, and child abuse. There was no encouragement for anything such as college or career. It was unspoken, yet understood, that ours was a life of struggle followed by early death from addiction. For my parents’ generation, that meant full-blown alcoholism. In my generation, drugs were added to the fatal mix. It felt like the family curse. My uncle Bobby Gene was fifty-one when alcohol took him out. My mother Evelyn was fifty-eight. My uncle Tommy was thirty-eight. My cousin Ricky was twenty-four when he died of an overdose.

For some, the weight of shame and addiction is just too much to bear. My dad’s brother Joe was thirty years old the day he stood in the backyard, placed the barrel of a shotgun under his chin and pulled the trigger. It’s unnerving that my cousin Morrie was the very same age when he ended his own life the same way. And yet, the family remained strangely silent about the devastating cycle of alcoholism and general insanity of it all. This life was the only life we knew, maybe because it was just too much hard work to crawl out from under the rubble. But it can be done. I have done it in my own life.

I have, by God’s grace, been able to break the cycle and seek healing and freedom from the shame that hovers like a cloud in the life of exile. It began when I woke up one morning being beaten in a van by a low-level drug dealer. I stumbled out of the van and looked around. It was early morning. The air was crisp and cool. I stood there in silence with the taste of blood in my mouth. I wiped the passenger-side mirror clear enough to see my reflection and inspect the damage. It didn’t look too bad, not yet anyway.

“It was unspoken, yet understood, that ours was a life of struggle followed by early death from addiction.”

Stooping in front of that van mirror in the cold morning air, something happened. Even in my dazed state I knew that if something didn’t change, nothing was going to change and eventually I would end up dead. It might come from an overdose, or from my body finally collapsing under the weight of nearly three decades of addiction, or maybe it would happen with a bullet in the head from a drug deal gone bad. Either way, it was only a matter of time and circumstance. In the end, the monster of addiction would have the final say. I knew that I was at a crossroads, and that I couldn’t just stand there and wait for death to take me out like it had taken so many of my friends. So, with nowhere to go—I started walking.

The day that would change my life began with me being beaten in the back of a van. Sometimes God’s grace looks like that.

The people I have met behind bars have experienced a similar sense of shame and exile. They have been judged, condemned, branded as “bad,” and largely discarded as unworthy and unredeemable. They have been pushed around by the circumstances of their lives and pushed aside by the mainstream. They have been banished to the wasteland of our jails and prisons, out of sight of the larger community. This is large-scale exile. It’s called mass incarceration. The Los Angeles County Jail System, which now houses people sentenced to prison terms in addition to those in the court process, has an inmate population of roughly 18,000. It is the largest mass incarceration facility in the world.

“The day that would change my life began with me being beaten in the back of a van. Sometimes God’s grace looks like that.”

On a national scale, according to the 2017 Prison Policy Initiative Report, the American criminal justice system holds more than 2.3 million people in 1,719 state prisons, 102 federal prisons, 901 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,163 local jails and 76 Indian Country jails as well as in military prisons, immigration detention facilities, civil commitment centers and prisons in the U.S. territories. These facilities are filled with our societal failings. Because of our inability or unwillingness to properly address the real issues of racism, poverty, addiction, and mental illness, we instead try to hide these failings in our jails and prisons. We try to incarcerate our way around the problems, at the cost of human dignity and life.

Many of those living in exile behind bars have known other forms of exile in their lives before they were ever locked up. And the same is true for those lucky enough or privileged enough to avoid incarceration. Those who have been abused as children—whether physically, sexually, or emotionally—know what it’s like to live in the exile of shame. I know from experience about the lonely desperation of addiction and homelessness.

Women (and men) who have suffered from domestic violence know of the prison of silent shame, fear, and powerlessness. People living in poverty know what it feels like to stand outside the mainstream; sadly, most first realized it as young children. Mental illness brings with it a challenge to find one’s place in a world that can never fully understand the silent struggle of isolation and confusion. And racism is a corrosive and shameful thread that continues to eat away at the very core of our common humanity. Slavery has never been abolished in our country; one need only step inside any jail or prison to see clear evidence of this truth. My good friend, a retired bishop in the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles, the Rt. Rev. Chet Talton, once said, “Racism is America’s fundamental sin.” Sadly, this is as true today as when I first heard him say it.

“We try to incarcerate our way around the problems, at the cost of human dignity and life. ”

All of these forms of exile are tributaries that feed into the ocean of mass exile behind bars. So just how do we sing our song in the alien soil of exile that is the prison-industrial complex? How do we lift our voices that speak of the struggle, the heartbreak, the joy, the brokenness, the grace, and the beauty of life in exile?

In Sister Greta Ronningen’s book Free on the Inside: Finding God Behind Bars, she describes one of the most important elements of healing wounds: to first find a safe and sacred place to tell our story. In order to move from brokenness to healing and wholeness, we must be able to tell our story in a safe and sacred space of compassion and love. Many of the friends I have had the honor to walk with during their time of incarceration tell me that they have never had anyone really listen to them. They have never had anyone value what they had to say.

That is why our Prism Restorative Justice ministry in the jails is primarily one of compassionate presence and holy listening. Our only desire is for those we are with is that they would know love. Sometimes the stories are spoken from our lips, and sometimes our tears are our words. This is about speaking truth and seeking truth. It’s about pulling the harps down from the trees and singing our song, the song we sing together.

Another essential element of true restorative justice is a welcomed return to community. Our story is about getting to know people in new ways and inspiring a depth of love and compassion for the “stranger” in our midst that can inspire flourishing in community. It’s about all of us returning from exile, not just those behind prison walls. We all have our own prisons; all of us are exiled in little ways, or not-so-little ways. The journey is about coming home—for all of us.

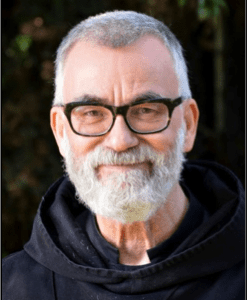

The Reverend Dennis Gibbs’s new book Oblivion: Grace in Exile with a Monk Behind Bars, is now available for order. All proceeds go toward furthering the work of Prism Restorative Justice in the jails.

“So just how do we sing our song in the alien soil of exile that is the prison-industrial complex?”