Holy Tears

One of the most intimate and memorable moments of worship came in a seemingly unlikely place, although I have come to expect such things from God. I have heard it said before, and it is true for me that I am constantly amazed yet seldom surprised. The place was the dayroom on the psychiatric floor of the clinic in Twin Towers Correctional Facility. Twin Towers—one of six L.A. County Jail facilities—houses about 4,000 inmates, both male and female, all of whom are diagnosed with varying degrees of psychological challenges. It is the largest mental health facility in the United States, and it’s a jail. This is clear and alarming evidence that we are incarcerating our mentally ill in numbers we have never seen before. It both saddens and disturbs me that because of our failing as a society to properly deal with issues such as mental illness, we instead just throw people in jail. But using incarceration as an answer to our mental health care challenge doesn’t make people’s problems go away. As Angela Davis said so many years ago, the only thing that disappears is the human being.

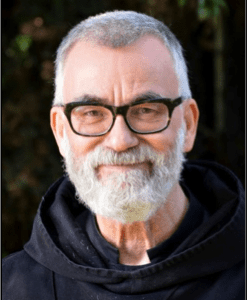

I have met thousands of these “invisible” people. By invisible, I mean people who are tucked away in jails and institutions, hidden from the mainstream view. As an Episcopal monk and director of Prism Restorative Justice, a ministry that provides spiritual care for the incarcerated, I am here to say that there are no throwaway people. There are only people who, regardless of who they are or what they may or may not have done, are held in God’s grace and love as God’s beloved children. Chavez is one such person.

I am here to say that there are no throwaway people.

Chavez spoke only broken English. She was deeply fractured from the tragic and traumatic events that had landed her in jail. Each Tuesday morning she would come to my intimate gathering for worship in the psych unit on the fourth floor with four or five others, shuffling into the small recreation room draped in dark blue “suicide gowns” fashioned out of the same material used for furniture pads and fastened only with Velcro strips. It’s bizarre that prisons refer to these as gowns. They are terribly degrading and yet, oddly, the women seemed to somehow transcend the degradation with grace, in a way that helped me to not see the gown, but only the person.

Of those who attended, Chavez was the one who, while never saying anything, always helped me set the altar, which was a three-by-three-foot square table. Together, we spread the white altar covering, liturgical colored band and fair linen. She always did it with such gentle intention and reverence. She loved placing the cross and she always sat directly across from me, with only the width of the table separating us. During Eucharist she fixed her gaze upon that cross.

Once, while we were taking a quiet moment of reflection, as we always did after sharing Communion, I opened my eyes to the sight of the white fair linen. Suddenly and silently I saw her teardrop land. I heard Chavez whisper, “Thank you, Jesus.” I knew that God’s tears were mingling with her own in that moment. God’s grace was with her pain and her comfort.

Twin Towers is a place where the awareness of one’s need of God’s healing is very real—for both Chavez and myself. It is also a place where the experience of that grace is very real. And there are moments when this Divine Grace cuts through all of the complexities of life. Watching Chavez cry, I was allowed to experience the stunning and breathtaking reality of God’s love up close.

Twin Towers is a place where the awareness of one’s need of God’s healing is very real—for both Chavez and myself.

Holy Water

Those living in exile in jail, like many others in the world, have a deep longing for such truth. The last thing these people whom Jesus referred to as “the least of these who are my family” need is to be pushed outside the circle. What they need—what we all need—is love. None of us are without our own shortcomings, but no matter who we are or what we have done, no one is beyond God’s grace and love. Our task is to be instruments of that love for one another. Final judgment is God’s work; ours is something different. The people we walk with in the jails are thirsty for this kind of redemptive love. They, like all of us, are thirsty for the clear water from the cup of salvation. This is the water that inmates and I share with each other as we worship, pray, and receive the Eucharist side by side.

“Let anyone who is thirsty come to me and drink. Whoever believes in me, as Scripture has said, rivers of living water will flow from within them.” John 7:37-38

Baptisms have become increasingly common for us at Prism Restorative Justice. I’m sure it has something to do with our unconditional and all-inclusive presence in the jails. For some inmates, it is the first time in life that they have found a spiritual community that welcomes everyone as they are. For others, it might be that they feel safe to reclaim who they are and free to rediscover their faith. Quite often people are drawn to the baptismal waters because they realize that the transformation they are experiencing stems from living our common life together based on the life and teachings of Jesus. Whatever it is that brings people to this important moment, it is a joyful day, and I am quite sure that all the company of heaven rejoices when one finds their footing on the path from brokenness to healing and wholeness.

They, like all of us, are thirsty for the clear water from the cup of salvation.

Ricky, when I first met him, was about as tough as they come around here. I used to good-naturedly refer to him as a “cowboy,” which he accepted with easy pride. He’s an intimidating young man, strong and cocky with the scars to prove that he’s been through more than a few rough rides. He once told me that he never felt more powerful than when he had a bag of dope in his pocket and a gun in his waist-band. But he worked hard to change and, like a lot of men who have been hardened by the life, if you stay with them—I mean really stay with them long enough—you will see the sweetness. You will see the little boy in them.

Like most of the men I spend time with, Ricky has been my teacher as I watch his heart of stone become one of tender human flesh. I have seen him struggle to turn away from the violence that he has known so well in his life. I have also heard about it when he was in the “hole” (solitary confinement) again for reverting to that violence and swinging on someone whom he felt disrespected him. These kinds of toxic reactions most likely come from deep wounds that have never been tended and healed. Most of the men in jail have their own version of these deep wounds and have never been taught how to heal them.

Ricky’s back on the row after his time in the hole. He is, like most of us, a work in progress. On this particular day, the altar was set with fair linen again in a small dayroom located at the end of the row where Ricky lived. Four of us gathered to share this holy experience of baptism. Another table—cleaned with paper towels and water—was dressed for the occasion draped in gold and white. The sterling silver ciborium (a small box holding the Body of Christ) and lavabo (water bowl) glistened in the otherwise drab environment. It was like a divine light shone on that makeshift altar, illumining the entire space. We began the Holy Eucharist amid the noise and chaos of the row where forty other men were carrying on with their life, yelling back and forth and from the upper and lower tiers. But in this space even the cacophony of noise sounded sacred. It was as if all of the life of those rows was joining in the chorus of angels.

We began the Holy Eucharist amid the noise and chaos of the row where forty other men were carrying on with their life.

Once again, from inside a prison, I watched holy water flow. This time it flowed from the silver lavabo over Ricky’s head, and it flowed from our eyes. Once again, the awareness of the soul’s need for healing was met by Divine Grace, and streams of living water flowed through our collective heart. I couldn’t help but notice a tiny spot of water that had once again found a resting place on the linen. I remembered Chavez and was reminded that we are all connected in mysterious and wonderful ways. This is worship in the L.A. County Jail. This is grace in exile.