On April 19th, 1775 – war was coming to Lexington, Massachusetts. The 77 hastily armed colonists arrived first. The sun began to rise, and with it came the sound of a marching war machine. The militaristically-naked colonists gaped at the more than 700 redcoats that faced them, weapons drawn. A sneering British major had approached within shouting distance and yelled, “Throw down your arms! Ye villains, ye rebels.” Within moments, firing started on both sides. Eight colonists lay dead. The British force advanced and set fire to the town. As soon as they advanced beyond the town however, they were met with the veritable thousands of “minutemen” who had assembled nearby. Quickly deployed and burning to protect their freedom, the minutemen overwhelmed the British force. In the days after, thousands more men were recruited in the local region. One of these men was a newly freed slave named Lemuel Haynes. A passionate Christian and Calvanist, Lemuel helped fight and tend to the wounded during the subsequent engagements. Seeing the blood and combat on the following few days – he vowed in his heart that he would fight to extend freedom and liberty to all men and women in the new colonies.

Abandoned and Loved

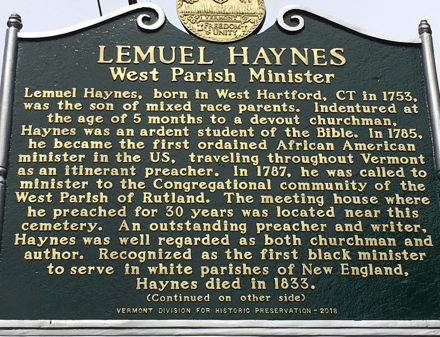

Lemuel Haynes went on to become the first ordained black pastor in American History. He was the first black man to receive a degree, and the first black man to pastor any congregation. He was the first black american to be internationally published, and probably the first black american to be published at all. He was the first black american to speak boldy and truthfully about the degradation of slavery and the callous contradictions of the United State’s leaders.

Lemuel Haynes’ life is a life of many firsts in America. Abandoned at 5 months old by both his parents, Lemuel was a biracial baby who was indentured to a well-to-do and upstanding Christian Massachusetts farm family: The Rose’s. First hand accounts, along with Lemuel’s own writings, tell of a loving family, where Mrs. Rose loved Lemuel singularly, and treated him as a son. Scholars have reasonably concluded that Lemuel’s mother was a white woman of prominence locally, and was unable to admit to sexual scandal, but was willing to do what she could to set her son up with a life better than chattel slavery. Later on in life, Lemuel would describe his distraught bitterness at the passing of his adoptive mother, Mrs. Rose. She had given him the love and care he so desperately wanted as a young child who experienced the attachment anxiety of separation from both parents at such a young age.

He received limited schooling, and infrequent religious instruction. Even as a child – he wrote and delivered his own witty sermons and orations. While he kept most of these personal sermons, they perished in a fire later on in his life. The duty of reading sermons aloud was shifted from person to person in their smaller farm community. One Sunday he gave a rousing, intelligent and heart-wrenching sermon to the gathered family, except everyone took it for granted that he had taken it from a book, journal or sermon collection from one of the many authors they normally read from. When questioned who wrote the sermon he read, he revealed he had done so himself. His theological fervor had already taken root at a young age.

Upon turning 21, his servitude was fulfilled and he was given his freedom, he enlisted in the local militia, and built a stone house nearby. He was soon after called upon to fight the British. While serving, he was involved in several major skirmishes and campaigns. During his free time – he often wrote poetry. He was recruited by Ethan Allen’s Green Mountain Boys, and saw limited action. Eventually sent home, to Granville, MA due to illness, he returned to his farming duties and began studying Greek and Latin with two local reverends who agreed to oversee his theological education. His active religious mind and oratorical talent could not be denied or minimized. Everyone in his community encouraged him to pursue ministry and pastorship, because from a young age they had witnessed his ardent fervor. He passed the pastoral licensing exam easily, and was the first black man to be awarded a pastorship in America.

Haynes’ Politics and Religious Futurism.

In the Bible, Lemuel means, “belonging to God.” King Lemuel is mentioned once, in proverbs. Attached to this scripture is an exhortation from a mother to her son, to belong to God, and never leave. Lemuel Haynes viewed this as his personal calling. He took the first 10 verses of Proverbs 31, as his own personal call and exhortation to live a life belonging to God.

In 1776, after reading the declaration of Independence, and before his official ministry, he was so inspired that he wrote his own essay, the first abolitionist essay ever published in the new nation of America, called, “Liberty Further Extended” His purview, as the name suggests, made the strongest argument for why the Declaration of Independence needed to specifically include enslaved peoples.

For Haynes, politics did come to the pulpit often. He refused to support Thomas Jefferson as president, because Jefferson was a slave owner. He was removed from his congregation for “mixing church and politics.” All along, he had shown that slavery wasn’t a political issue at all. It was a God issue. He truly was a cultural futurist, and light years ahead of all his contemporaries. He stood against colonization–sending free African-Americans and Blacks back to Africa to colonize remote settlements–for all the same reasons we now see it was a disaster. He opposed every kind of religious sectarianism that supported slavery. He centered his theology around God, and his abolitionist views flowed freely from his witty and deep political and religious commentary.

Haynes was the first black abolitionist to reject slavery on purely theological grounds, rather than hiding behind social, economic, or civic arguments for the abolition of slavery. He left behind a literary tapestry of essays and works that influenced minds, spoke out on important issues, and helped direct local government. Local leaders sat under his sermons, and God used his voice like a megaphone. His writing was prolific, and we have a flowing stream of sermons, social commentary, political dissertations , and musings surrounding the direction of the new country of America. Politically, he supported only Federalist candidates Washington and Adams. Adams owned no slaves, and was against it. While Washington on the other hand had risked his life, his health, and his entire estate, in order to secure the freedom of the country, and upon his death, had emancipated any slave that had been on his farm.

In the Bible, Lemuel means, “belonging to God.” King Lemuel is mentioned once, in proverbs. Attached to this scripture is an exhortation from a mother to her son, to belong to God, and never leave. Lemuel Haynes viewed this as his personal calling.

Vocation and Ministry

After pastoring an all-white Connecticut church for several years, with rousing, standing-room-only audiences, a few troublemakers in the church drove him away for his outspoken belief that slavery was a sin. Despite his departure, many congregants expressed regret and remorse that they didn’t speak up on his behalf.

But God was only getting started. It was at this time, in 1783, that Hayne’s ministry began to grow. A young white woman, good friend and schoolteacher, Elizabeth Babbitt, moved from her home in order to be near Haynes. Just 21 years old, she proposed to Haynes, breaking several barriers and cultural norms in the process. She waited to propose until they had reached Connecticut because of the several miscegenetic laws that Massachusetts had. He joyfully accepted and they had 10 children together.

Elizabeth’s motivations for moving and proposing are unclear, aside from a very obvious passionate love she had for him. She proved to further legitimize his ministry in the eyes of many–sadly due in part to the fact that she was white–since she was a school teacher, which allowed Lemuel to write and publish works at home. After leaving the church in Connecticut, they set out for the frontier state of Vermont.

Lemuel spent the next 30 years pastoring a church in Vermont. During his tenure there, he preached and worshipped with many congregational churches of blacks and whites that worshipped together, a historical phenomenon most people are unaware took place at the time. His reputation steadily grew. Text from the National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form for the Lemuel Haynes House in South Rutland, New York, tells the story like this:

“He was in demand to speak on political occasions and his sermons, through which he defended the gospels according to Jonathan Edwards and George Washington, were often given serious attention by the press.”

Haynes left the Rutland ministry to enter the final phase of his vocation. He was in high demand as a pastor and speaker all over Vermont. He pastored another church in South Granville, New York. His church grew and so did his ministry of spiritual counseling, funerals, and weddings.

Slavery and Sin

Hayne’s outspoken and staunch religious rhetoric surrounding ‘slavery as a sin’ was published in newspapers around the 13 colonies. He held the title as one of the first African American’s to be published – and received an honorary degree from Middlebury college at a commencement speech in 1804. A Pastor named Reid S. Monaghan wrote a particularly compelling phrase on Lemuel’s life:

“As a biracial man, raising a biracial family he was granted a closer position in white society than most African Americans of his time. Yet this proximity also made the discrimination he faced all the more difficult as indicated by churches that would let him preach the gospel to them but would not let allow him to be in authority over them as their pastor.”

Haynes was the first black abolitionist to reject slavery on purely theological grounds, rather than hiding behind social, economic, or civic arguments for the abolition of slavery.

He truly believed, as the founders did, that life without liberty is no life at all. He was trying to impart that to anyone who would listen around him. Give me liberty or give me death. Yet the nation around him had only deaf ears. The fervor of revolution and liberty crowded out and disenfranchised the one group who had been deprived of liberty since the beginning, the black community.

Haynes’ service in the military allowed him to see first hand the death and war that liberty required. He came to realize that liberty from slavery would come at a cost. He saw no greater calling than to fight for others to pursue the same freedom he had tasted, even if it was slight. As he grew older, so did his frustrations. Haynes opened wide the door of criticism during a meeting with the Washington Benevolent Society, when speaking of James Madison:

“We feel a pity and compassion for our brethren in slavery, and pray for their deliverance and emancipation; but we further inquire, will going to war obtain the object? Or is it a crime sufficient to shed blood? Our president can talk feelingly on the subject of impressment of our seamen. I am glad to have him feel for them. Yet in his own state, Virginia, there were in the year 1800, no less than three hundred forty-three thousand, seven hundred ninety-six human beings holden in bondage for life!“

Scholars will note that Haynes’ stance and arguments would have been categorized at the time as “radical abolitionism”. He used religious arguments to bolster political ones – and made a clear departure from any less radical tones that other abolitionists took during his time – this can mostly be seen in his writing Dissimulation Illustrated.

“He was original in his ideas– gentle in his reproofs and powerful in his rebukes. His talent at satire was prodigious, and when he found it necessary to employ it, his opponents would shrink away before him and leave him master of the field.”

Death and Legacy

Timothy Mather Cooley (referred to as Reverend Cooley) was Haynes’ chief biographer and spent many moments with him in the evening years of his life. He recounts a time when Haynes lost many sermons, manuscripts and letters in a terrible fire, most of them un-published. Haynes responded, “Brother, they gave more light from the fire then they ever gave from the pulpit.”

Haynes passed away at the age of 80. The last 11 years of his ministry were by far the most gratifying. The following words appeared in The Liberator a month after Reverend Hayne’s death in 1833. They speak to how people were affected by his life, and how many christians considered him their spiritual father. He truly had done so much to destroy the boundaries of race with his own congregation and those who he spoke to: “ He was original in his ideas– gentle in his reproofs and powerful in his rebukes. His talent at satire was prodigious, and when he found it necessary to employ it, his opponents would shrink away before him and leave him master of the field.”

When addressing his race – those who loved him learned to confront it head-on as he himself had done “(…)But Mr. Haynes was a man of color. Had he not, therefore, a mind like that of other men? Let those who listened to his thrilling eloquence, answer! He suffered much in consequence of cruel prejudice against those of his color, but he never complained. He was a spirit which soared above such things.

The final line read: “He knew there was a heaven of joy where differences of color would not exist, or if they did, it would be no hindrance to the intimate union of saints.”

He challenged people’s theological equilibriums, convicted apathetic slave-holders, and sought to bring everyone he knew back to the basic grace he had so generously experienced through Christ.

Lemuel Haynes belonged to God. He is commemorated as the first black clergyman to be ordained by any religious organization. He was a pastor for the most widespread church in New England at the time, the Congregationalist Church. He was the first black minister of an all white congregation. First black man to receive a Masters of Arts degree, and first published radical abolitionist. In desperate and uneven times, he devoted his life to God, and God used him in ways no one could have dreamed. Imagine the sheer number of lives he touched while he was in pastorship. He challenged people’s theological equilibriums, convicted apathetic slave-holders, and sought to bring everyone he knew back to the basic grace he had so generously experienced through Christ. No sin could out-do Christ’s grace, and nothing can conquer his love. Lemuel Haynes lived an unconquerable life, because he was part of God’s unconquerable love.